Who needs the Metaverse? Meet the people still living on Second Life

Mark Zuckerberg’s grand vision for an online existence has been laughed off as a corporate folly. Meanwhile, those still existing happily on a virtual world launched 20 years ago may be wondering what all the fuss is about …

On 14 November 2006, 5,000 IBM employees assembled in a digital recreation of the 15th-century Chinese imperial palace known as the Forbidden City. They had come to hear IBM’s CEO, Sam Palmisano, deliver a speech. Palmisano’s physical body was in Beijing at the time, but he addressed most of his audience inside Second Life, the online social world that had launched three years earlier. Palmisano’s trim avatar wore tortoiseshell-frame glasses and a tailored pinstripe suit. He faced a crowd of digital, animated dolls dressed in the business attire of the day: black heels, pencil-line shirts, Windsor-knotted ties. Looming out of the throng at the back stood a 10ft IBM employee, his digital face plastered in Gene Simmons-style white makeup, with shoulder-length, Sonic-blue hair.

It was a historic moment, a journalist for Bloomberg reported at the time: Palmisano was “the first big-league CEO” to stage a company-wide meeting in Second Life – “the most popular of a handful of new-fangled 3D online virtual worlds”. IBM, just like any other denizen of Second Life, paid ground rent to own a “region” of the game, one region representing 6.5 hectares of digital turf, currently rented at $166 (£134) a month. Renters could build whatever they wanted on their turf.

The pitch proved attractive. While in cities like New York or London you might never own a flat, in Second Life you could design, build and inhabit a mansion. Institutions followed. Some used their space to stage art exhibitions and theatrical performances; others built kink palaces. The retail outlet American Apparel opened a virtual store on a private island called Lerappa – “Apparel” spelt backwards – selling costumes for avatars. The US universities MIT and Stanford established faculties in Second Life. Someone claiming to represent the far-right French National Front joined in (their HQ was the site of virtual clashes with anti-racism demonstrators in 2007). The world used its own currency – the Linden dollar, withdrawable into local currencies – to establish a global, user-to-user economy. Transactions and withdrawals were subject to a tiny fee, which contributed to the cost of server maintenance – a revolutionary, influential business model.

While Second Life’s world was viewed by many as rudimentary and its inhabitants eccentric, in hindsight it represented a bold, pioneering experiment, launched while Facebook was still a website for rating the attractiveness of Harvard students. It remains both the first and the most successful manifestation of a so-called metaverse, a compelling if somewhat imprecise term coined by American writer Neal Stephenson in his 1992 sci-fi novel Snow Crash. Definitions vary, but most experts agree the metaverse is, put simply, the internet made metropolis: an immersive, contiguous representation of data and the active user communities within. One might walk from, say, eBay marketplace to YouTube cineplex; or take a virtual Uber from the great library of Wikipedia to the twin towers of TikTok and Instagram. No need for a thousand logins and passwords: in this Internet World theme park, each of us could embody a single body and consistent identity.

Second Life did not replace the internet in this way. And even at the height of its popularity in the late 2000s, it attracted only around a million monthly users – a fraction of the number enjoyed by some online video games (the makers of Fortnite claim a consistent 80 million) and far fewer than would be necessary to sustain a business such as, say, Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook. But the dream of a coordinated manifestation of websites and users, built on current technologies (VR headsets, blockchains, cryptocurrencies and all) and opening unprecedented opportunities to virtual landowners, marketers and advertisers, has persisted at the highest levels of corporate Silicon Valley, up to and including Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg.

Zuckerberg first outlined his vision for the Metaverse, the “successor to the mobile internet”, in 2021. According to Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, the project would take a decade to revolutionise the way we browse the web. But less than two years and $36bn later, the project has stalled, with little to show for it. User numbers for Horizon Worlds – Meta’s first draft of an interconnected world entered via a VR headset – have steadily declined during the past year. According to internal documents, most visitors do not return after the first month and a feature to reward users who have created content within Horizon Worlds generated just $470 globally in revenue in its first year. Zuckerberg recently announced 21,000 redundancies and hinted that all Meta employees may soon be required to return to physical offices, a rather self-sabotaging policy at a company committed to erasing the distinction between the physical and digital. As it sheds employees and investor focus impatiently shifts to the get-richer-quicker possibilities of generative AI, the vision fades. Almost every national newspaper has run a variation on the article: “Whatever happened to the metaverse?”

Yet Second Life – and its more modest vision of an Internet World – persists. This month it celebrates its 20th anniversary; a mobile version is set for release this year and its developer, Linden Lab, estimates the virtual world’s GDP to be $650m. According to the company, around 185m items are sold each year in the Second Life marketplace, with an average cost of $2 each, and 1.6m transactions – also including tipping, services, currency trades – occur every day. During the pandemic, new registrations soared, with close to a million visitors logging in each month and some building viable businesses trading in virtual goods and services. This is nothing close to the world-conquering figures Zuckerberg would need to justify his sunk costs, but Second Life has nonetheless endured as a profitable and, crucially, populated metaverse.

And while the world’s largest tech companies continue to seek ways to more intrusively monitor and monetise our online lives, the metaverse idea is unlikely ever to disappear.

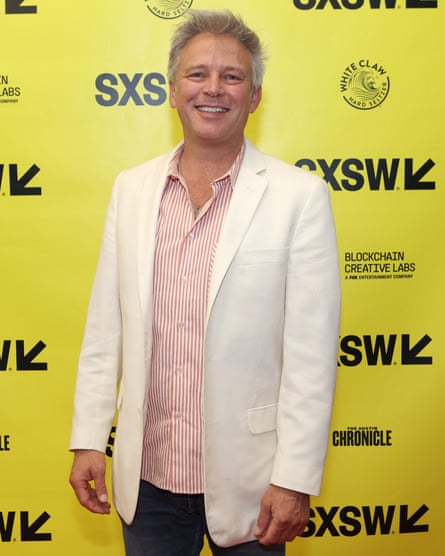

Second Life’s creator, Philip Rosedale, claims his vision of an accessible digital utopia long predates Stephenson’s invention of the word “metaverse”. As a child, Rosedale – who, having left Linden Lab in 2010, returned in January 2022 as a strategic adviser – built go-karts and gadgets. He installed a parabolic antenna on the roof of his parents’ house which he could angle to eavesdrop on friends’ conversations down the street.

Rosedale – who, at 54, still has the appearance of a boy-genius inventor, with colourful glasses and a cartoonish floppy shock of grey hair – was also a dreamer. “I had dreams in which I imagined myself building in space, wearing a spacesuit, using tools I had on my belt to make walls appear and move surfaces around,” he recalls, speaking over Zoom from Linden Lab’s office in San Francisco. “I could build great architectural structures in space. But the idea in my mind was always that was something you could do inside the computer.”

Rosedale read both science and science fiction: Stephen Wolfram’s work on cellular automata in Scientific American, Vernor Vinge’s Rainbows End, William Gibson’s Neuromancer. “I became fascinated by this idea of creating a world that had some simple, low-level rules, but that would become alive from these elemental basics, you know, like a real world does.” When, in 1992, his wife bought him a copy of Snow Crash, she told him: “You’re going to love this: a science fiction book about that thing you’re always working on.”

Two years later Rosedale moved to San Francisco. “The first thing I wanted to do, of course, was use the internet to create a giant pool of server machines to simulate an immense world,” he says. “But even I was not crazy enough to try to do that in the early 90s, when the internet was still incredibly slow and computers were unable to properly render worlds in 3D.” By the time Rosedale founded Linden Lab at the turn of the century, he felt the technology was nearly ready.

Persistent online video game worlds were becoming commonplace (World of Warcraft, the most famous, launched a year after Second Life). While he wanted visitors to stake plots of virtual land and build virtual homes, Rosedale was determined Second Life would not become a video game filled with quests and errands. He wanted the creativity to be user generated, not prescribed – a place, perhaps, where people might try out new identities, proclivities and modes of escapism.

Still, Rosedale kept a close eye on video games, which provided the inspiration for Second Life’s burgeoning economy. “EverQuest, which was a well-known online game before World of Warcraft, had an economy,” he says. “There was a common meeting area people used as a marketplace, where they would cry their wares in text. That was one reason I was convinced we’d need to use an open economy, because it would allow for very complex outcomes.” A marketplace, he reasoned, would provide incentive for users to “build weird things”, then sell them to each other. “I tried to not get in the way of people being their own creators of narrative and content.”

On Second Life’s launch in 2003, Rosedale’s plans to pay for the project were unsophisticated. Initially, Linden Lab charged visitors a “basic access” fee of $9.95, with monthly premium subscriptions of $9.95 thereafter (or $6 if paid annually). After a year, the company switched to a real-estate model. Anyone could visit for free, but those who wanted to own and shape pieces of the world had to pay. Land renters could do anything they wanted with their patch: erect a billboard, build a skyscraper, dig a mine, even run a company. “That turned out to be a great business model,” Rosedale says. “The people buying land were happy to pay for it because they were hosting other things on it, often to make money.” Some opened stores filled with digital outfits; others became estate agents, selling or renting land in desirable locations. In 2006, BusinessWeek featured the first Second Life millionaire on its cover.

Linden Lab won’t provide a breakdown of its current revenue, but Second Life generates income from several sources in its virtual economy: land sales, maintenance, fees on certain transactions, premium subscriptions. The remainder comes from tiny fees added to every transaction made or by any user attempting to cash out. “These are typically single-digit percentages,” says Rosedale, who points out that Second Life has higher revenues-per-user than YouTube or Facebook, yet does not rely on advertising driven by behavioural targeting and surveillance, which he describes as deeply unethical practices the public would never accept in the physical world.

It’s unclear, Rosedale says, which corporate interest first acquired land in Second Life: “People just use their credit cards, you know. It’s direct-to-consumer.” He remembers the first noteworthy acquisition, however. “We auctioned off an island.” A London-based marketing and content development company, Rivers Run Red, bought it for an estimated $1,600. “At the time it seemed like a lot,” Rosedale recalls. “And I remember when people found out it was a real company, they were, like, super pissed. Everyone was up in arms.” (In 2008 Rivers Run Red partnered with Linden Lab to launch Immersive Workspaces 2.0, virtual meeting rooms in Second Life that could be tailored to the specific needs of a client – an idea that now seems eerily prescient, and another key area of interest for Zuckerberg’s Meta.)

The idea of encouraging real-world businesses to set up in the metaverse, turning their webstores into polygonal buildings, seems key to Zuckerburg’s vision today, too. Meta’s ecstatic 2022 Super Bowl ad featured a mascot dog, forced into redundancy by a restaurant closure, suddenly able to reunite with former colleagues in the Metaverse, a virtual high street on which his former place of work had been miraculously reopened. The message seemed to be that, as the real world becomes ever bleaker and more disconnected, a new digital world, accessed via VR headsets, offers a place to reconnect with old friends and restore bankrupt businesses.

Yet for every true believer there are 50 detractors for whom every metaverse is a joke, or at least a solution looking for a problem.

To people of my age – “digital natives” who grew up at the same time as the internet – Second Life was a punchline: World of Warcraft but with terrible graphics and no purpose. Why would you want to hang out there, laying white picket fences with bald men pretending to be furries (there are 18,000 items for sale in Second Life stores under the tag “Furry”), when you could be rampaging across the hills of Azeroth, broadsword held aloft, on a mission to take down a giant cave troll?

Unlike the vast, interconnected video games of the time, with their arcane rules and Dungeons & Dragons-esque aromas, Second Life was beloved by mainstream journalists who could more easily communicate its appeal – and report human, sometimes salacious stories – to a non-game-playing audience. Even completely offline people could understand the Daily Mail headline: “Mom-of-four dumps husband for pole dancer she met in online game Second Life”. Nobody at the time referred to Second Life as a metaverse; it was just another online space in which slightly nerdy misfits found community – albeit one that, via its crude graphical representations, made the usual sexual frisson found in online spaces manifest via explicit digital representations.

Second Life has never quite shrugged off that slightly seedy, tragic association. Yet during lockdown, when many people craved social connection, visitor numbers began to grow again. Wagner James Au worked for three years as a journalist embedded in the virtual world and has written a book, Making a Metaverse That Matters, charting Second Life’s rise and fall and rise. According to him, today the population skews middle-aged and around 20% of users have a disability that makes real-world interaction difficult.

While other projects have shrunk and closed, Au believes Second Life has endured because of its capacity to facilitate human creativity. “The power and freedom of its creation tools encourages sub-communities to grow, thrive and adhere in the virtual world,” he says. Neither is it seen as a rip-off: “Strong and fair creator economies are rare among metaverse platforms. But Second Life creators earn roughly as much as Linden Lab.”

Most people first join Second Life out of curiosity or boredom, but the reasons for staying are as numerous as the residents, as Fabrizio Laceiras (known as Aufwie) tells me. A musician based in Birmingham, Aufwie, 26, first visited Second Life aged 12. After experiencing bullying at school, he found it hard to make friends and socialise. “Second Life offered a safe environment in which I could be social on my own terms,” he says. Music was his chosen icebreaker. “I would just pop by some virtual land that allowed microphone usage and start playing guitar and singing until someone approached, and we’d start talking.” Often Aufwie’s performances drew a small crowd, so a friend encouraged him to play a proper concert, building a small stage on her land where he could perform. The pair chose a date and time, and distributed leaflets beforehand. When 50 people turned up, Aufwie’s PC struggled to render the throng on screen: “I was forced to log out momentarily, which gave me a bit of time to process what was happening.”

Then, during the pandemic lock downs, Aufwie attended a Second Life concert staged by another user, known as Skye Galaxy, that inspired him to professionalize. He has now played at least 300 concerts in Second Life, and continues to receive bookings from users all around the world to play at their virtual events.

While the rise in new Second Life users has tailed off since lock down, it remains the largest non-video game virtual space predominantly populated by adults. Still, it never quite grew to the scale Rosedale had once believed inevitable. In 2006, he said of Second Life, in a quote that became infamous: “We see it as a platform that is, in many ways, better than the real world.”

There are many long-term users of Second Life who, to one degree or another, agree with the statement. For over a decade, one YouTuber, Draxtor, has recorded the stories of Second Life creators who choose to spend much of their day inside the virtual world, where they can find social connection or physical freedoms unavailable to them in the physical realm. Others, such as Erik Mondrian, a former graduate student at CalArts, have found in Second Life a place for self-expression. Mondrian created a series of elegiac films of Second Life structures and locations accompanied by poetic readings, part of a long tradition of artworks created within and around the virtual world. He remembers the date he made an account: 23 March 2005. He picked his real first name and chose “Mondrian” after his favorite artist, from a drop-down list of options. (In 2017, he tells me, he had his name legally changed to Erik Mondrian.)

In the 18 years since he first made an account, he has drifted in and out of Second Life. “Two things kept me coming back, even after the occasional extended absence,” he says. “One was the people, the other the world; I have a strong fascination for place in all its forms, and I wanted to see more of the amazing virtual spaces people had made and continue to make here.”

Today, Rosedale admits he was naive to believe Second Life would become ubiquitous. “Of course, I shouted it from the rooftops, I was so youthfully excited with what was happening,” he says. “I figured everybody would want to have an avatar and that we would all spend a fraction of our lives in something like Second Life, or hopefully Second Life, for the purpose of doing an interview like this, or shopping, or hanging out with people or just having fun. We would wander and explore the world together. In retrospect, that didn’t happen.”

In part, this is because Rosedale overestimated the difficulty some people have with embodying an on-screen avatar. “I had a utopian belief that most people would be comfortable moving their objective selves into a digital reality,” he says. “That turned out to not be the case. Most choose to identify with only one embodied representation of themselves, and that is their physical body. The difficulty of sustaining a second identity is considerable and the number of people willing to do that is smaller than I thought in 2006. So I don’t think metaverses are going to be able to grow in a way that, for example, would sustain Facebook’s business enough for them to survive. They would need a good part of a billion people doing this.”

More positively, Rosedale says he was heartened to see how Second Life users predominantly get along. “It’s not divisive, or polarising,” he says. “Obviously I’m biased, but there is a lot of independent research to back this up. Second Life delivers on the dream that a lot of us had about the internet at the beginning, which was that it would be this civil, interesting, thoughtful place where people would, if anything, overcome differences between themselves and find new ground.”

This is where, he argues, the idea of a virtual world built in 3D space offers non-gimmicky advantages over a traditional social network. “In a virtual world you actually have neighbors,” he says. “And they have different personalities and come from different backgrounds, so what happens is people are forced to frequently interact with people who are different from them.” Compared with a Facebook group, which gathers like-minded individuals and encourages self-polarizing, Second Life forces interaction with a variety of users.

If it seems as though Rosedale has essentially invented the revolutionary concept of “a village”, he is quick to point out the virtue of virtuality is that there is no threat of physical altercation in disputes; this can encourage a bottom-up civility, easing the burden on traditional top-down moderation techniques deployed by the social media giants. “If somebody’s having an extremist gathering in Second Life, other people are going to wander by and challenge that, because it is occurring in the same physical space. That is a lot healthier than what we’ve seen with the echo chambers and hard boundaries of social media.”

Second Life, to Rosedale, affirms the essential virtues of humanity. “The fact is, most of us almost all of the time are good,” he says. “We’re social, we’re collaborative. Our primary reason for interacting with each other, even with strangers, is to help them. So it’s appalling to me that, via business motivation, we’ve actually managed to create these social media terrariums which manipulate people into being bad to each other, when it’s not their instinct.”

Rosedale believes a ubiquitous metaverse, whether it’s made by Zuckerberg or someone else, has the chance to be a kinder, less invasive online environment. But he fears that most of the companies working on such a project have missed one essential component of lasting success: the fact that people are as much creators as they are consumers. “There isn’t as yet any evidence that people want to have a purely consumptive entertainment experience in social virtual worlds,” he says. “I don’t think there’s any evidence in human history that you can get a billion people to just kind of sit there and veg out, watch stuff. You can’t get to the kind of usage levels that metaverse brands want to get to with a consumer non-participatory experience.”